The Argument from Scale (AS) Revisited, Part 4

In this version, I am going to make a subtle switch in the emphasis of the argument from the scale of the universe to the fact that humans don’t have a privileged position (spatially or temporally) in the universe.[1]

B: The Relevant Background Evidence

1. A physical universe, which operates according to natural laws and which supports the possibility of intelligent life, exists.

2. Human beings are a type of intelligent life and exist only on Earth.

3. God’s purpose(s) include the creation of embodied moral agents. [assumption]

E: The Evidence to be Explained

1. Non-Privileged Temporal Position: Humans did not exist right from the start of the universe.

2. Non-Privileged Spatial Position: The earth is not the center of the universe.

H: Rival Explanatory Hypotheses

theism (T): the hypothesis that there exists an omnipotent, omniscient, and morally perfect person (God) who created the universe.

metaphysical naturalism (N): the hypothesis that the universe is a closed system, which means that nothing that is not part of the natural world affects it.

Bayesian Argument Version 3 Formulated

(1) E is known to be true.

(2) Pr(E | N & B) > Pr(E | T & B).

(3) Pr(N | B) >= Pr(T | B).

(4) Therefore, Pr(N | E & B) > Pr(T | E & B). [From (2) and (3)]

(5) N entails that T is false.

(6) Therefore, other evidence held equal, Pr(T | E & B) < 0.5. [From (4) and (5)]

Defense of Premise 2

Notice that (2) does not entail the claim that we would expect human beings to have a privileged position in the universe if T is true. In other words, (2) does not entail Pr(E | T & B) < 0.5. I, for one, don’t think we have an antecedent reason on T to expect ~E. For all we know, if God exists, God may have created embodied moral agents throughout the universe. Indeed, for all we know, if God exists, God may have created embodied moral agents in an infinite number of physical universes!

Rather, (2) makes the much more modest, comparative claim that Pr(E | N & B) is greater than Pr(E | T & B). It is slightly more likely on T than on N, though unlikely on both, that there would be a reason why we would have a spatially or temporally privileged position (e.g., God’s desire to relate to us immediately after His creation of the universe rather than waiting billions of years, God’s desire to emphasize our importance to Him, etc.).

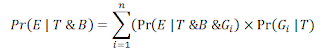

Elliott Sober made a point about design arguments which I think also applies to the AS: a proponent of the AS need not have “independent evidence that singles out a specification of the exact goals” of God.[2] Furthermore, she “may be uncertain as to which” of the statements about God’s goals G1, G2, …, Gn is correct.[3] However, since

a proponent of AS does have to show:

Can a proponent of AS show this? At first glance, this seems to be an impossible task. Just as it is easy to imagine antecedent reasons on T why humans would have a privileged position (e.g., God’s desire to relate to us immediately after His creation of the universe rather than waiting billions of years, God’s desire to emphasize our importance to Him, etc.), it is also easy to imagine antecedent reasons on T why humans would not have a privileged position (e.g., God’s desire that the non-human scale of the universe be an illustration of the vastness of God Himself, God’s desire to increase the maximize the beauty of the universe, etc.). Let’s call the former set of reasons “privilege-supporting reasons” and the latter “privilege-defeating reasons.” Based solely on the content of T and B, we have no reason to assign different probabilities to privilege-supporting reasons and privilege-defeating reasons.

While the last paragraph shows that we have no reason to give either set of reasons greater weight than the other, the privilege-defeating reasons are compatible with God giving many (to say the least) non-privileged positions to humans, while there are so few privileged positions.[5] Thus, the specific way in which humans have a non-privileged position in the universe is (slightly) more probable on N than on T, even if the non-privileged position of humans in the universe (generically speaking) is equally probable on both T and N.

Some Objections and Replies

Objection: AS assumes the existence of the universe, natural laws, the fine-tuning of the universe, etc., each of which are evidence for T and against N. Therefore, AS fails.

Reply: AS claims that E provides a prima facie reason for rejecting T, not an ultima facie one. Let F represent the set of facts presupposed by AS which are purportedly evidence for theism and against naturalism. Even if F is evidence favoring T over N, that does not contradict the statement that E is evidence favoring N over T. This is the case even if the former greatly outweighs the latter. Again, it could be the case that F is evidence favoring T over N, but, given F, more specific facts (like the non-privileged position of humans in the universe) are evidence favoring N over T.

The kernel of truth in this objection is that one’s assessment of the probabilities of T and N must be based on the total available evidence. This is why the conclusion of AS is that E merely provides a prima facie reason for rejecting theism (“other evidence held equal”); AS does not claim that E provides an ultima facie reason for rejecting T (i.e., all evidence considered).

Objection: If the universe were not as massive as it is, then life would have been impossible. First, there would be no life-essential elements. Second, there would either no stars or, if stars did exist, they would have been too large to allow planets suitable for life. Therefore, the universe has to be as massive as it is in order to support life.[6]

Reply: Given what we know about the laws of nature and the assumption that metaphysical naturalism is true, then the universe has to be as massive as it is in order to support life. On the assumption that T is true, however, there exists an omnipotent being who could have designed the universe with a different set of natural laws than the ones we actually have. So far from undercutting the AS, in one sense this objection actually provides an independent reason in support of (2).

Objection: Given what we know

about the laws of nature, it would have been impossible for humans to exist right from the start.

Reply: Again, given what we know about the laws of nature and the assumption that metaphysical naturalism is true, then it would have been physically impossible for humans to exist right from the start. On the assumption that T is true, however, there exists an omnipotent being who could have designed the universe with a different set of natural laws than the ones we actually have. So far from undercutting the AS, in one sense this objection actually provides an independent reason in support of (2).

Objection: (2) is either false or irrelevant to Christian theism, since Christian theologians have held that the natural world (creation) points to God. For example, the Psalms, Proverbs, and Romans seem to suggest, as have Christians throughout history, that creation “testifies” to its maker. Likewise, “Not only,” Calvin wrote, has God “sowed in men’s minds that seed of religion of which we have spoken but revealed himself and daily discloses himself in the whole workmanship of the universe. As a consequence, men cannot open their eyes without being compelled to see him” (1.5.1.).

Reply: This is not of obvious relevance to (2), since it is logically possible that creation testifies to its maker and (2) is true. For example, it’s possible that the beginning of the universe and the life-permitting conditions of the universe provide evidence favoring T over N; the scale of the universe provides evidence favoring N over T; and the total evidence about creation overwhelmingly favors T over N in such a way that humans are “compelled to see” God. Indeed, this possibility regarding the total evidence is logically compatible with the position, “All human beings know that God exists,” or even, “All human beings know that the Christian god exists.”

Objection: Certain Christian doctrines give us an antecedent reason–that is, a reason independent of the evidence for E–to expect, not just that creation testifies to its maker, but also the more specific fact of the non-human scale of the universe. For example, on Christian theism, God may not have given humans a privileged position in the universe for aesthetic reasons (cf. Gen 2:9) or in order to ‘illustrate’ the vastness and unfathomable mystery of God Himself. Therefore, (2) is either false or irrelevant to Christian theism.

Reply: This objection fails for two reasons.

First, if (2) is true, then (2) is, at least, relevant to Christian theism for the simple reason that Christian theism entails T. If B entails A and A is improbable, then B or any other set of beliefs which entail A are necessarily improbable.

Of course, it’s possible that Christian doctrines (or any other religious, ethical, metaphysical, or epistemological beliefs) could raise Pr(E | T & B) or lower Pr(E | N & B). The Weighted Average Principle (WAP) is a mechanism for evaluating the evidential relevance of other beliefs to (2):

Pr(E | T & B) = Pr(E | T & B & CD) x Pr(CD | T) + Pr(E | T & B & ~CD) x Pr(~CD | T)

If CD is some Christian doctrine, then Pr(E | T & B) will be an average of Pr(E | T & B & CD) and Pr(E | T & B & ~CD). It is not necessarily a straight average, however, because Pr(CD | T) and Pr(~CD | T) may not equal 1/2. For example, if Pr(CD | T) = 3/4 and Pr(~CD | T) =1/4, then Pr(E | T & B & CD) is given three times as much weight as Pr(E | T & B & ~CD) in calculating the average.[7]

The upshot is that, even if we assume that Pr(E | T & B & CD) is extremely high, we still have to address Pr(CD | T) and Pr(~CD | T) before we can conclude that CD raises Pr(E | T & B). I am unable to see how one could show that Pr(CD | T) > Pr(~CD | T), but I do not rule out the possibility that someone may discover a way to show that. The important point, however, is that it needs to be shown, not assumed.

Second, (2) is a comparative claim: it claims that Pr(E | T & B) is slightly more likely than Pr(E | N & B). Thus, arguments about the non-comparative value of Pr(E | T & B) are, by themselves, not relevant. Again, the whole point of the argument is to compare the ratio of Pr(E | N & B) to Pr(E | T & B). For example, hypothetically speaking, if Pr(E | T & B)=.99, it could still be the case that Pr(E | N & B)=.999, in which case (2) would still be true.

Notes

[1] This is based on a brief sketch of an AS in Paul Draper, “Seeking But Not Believing: Confessions of a Practicing Agnostic,” in Daniel Howard-Snyder and Paul K. Moser, eds., Divine Hiddenness: New Essays (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 199-200.

[2] Elliott Sober, “The Design Argument,” in Neil Manson, ed. God and Design, The Teleological Argument and Modern Science (New York: Routledge, 2003), 39.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] I owe this point to Paul Draper.

[6] Hugh Ross, “Mass Appeal: On How the Vastness of Space Makes It Possible for You to Be Here,” Salvo, https://salvomag.com/article/salvo20/mass-appeal (spotted June 15, 2012).

[7] Paul Draper, “More Pain and Pleasure: A Reply to Otte.” In Christian Faith and the Problem of Evil, ed. Peter van Inwagen (Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2004), 41-54.