Survival Researcher or Christian Apologist? Could You Tell the Difference? (Part 1 of 3)

Man is a credulous animal, and must believe something; in the absence of good grounds for belief, he will be satisfied with bad ones.

— Bertrand Russell, “An Outline of Intellectual Rubbish” (1943)

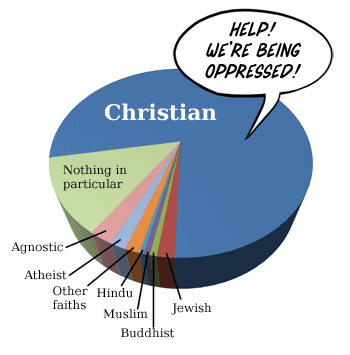

In my critique of the Bigelow Institute for Consciousness Studies (BICS) essay competition on the “best” evidence for life after death and my response to the summer and winter commentaries on it, I made reference to striking similarities between the arguments made by Christian fundamentalists and survival researchers (i.e., those who purport to investigate survival of bodily death scientifically). In this three-part guest post, I’d like to highlight or elaborate on fifteen or so examples of how those at the forefront of “scientific” research into an afterlife—or in BICS’ framing, the survival of human consciousness after death—have consistently used fallacious arguments that mirror parallel arguments prominent among fundamentalist Christians.

Here I’ll only note instances of fallacious reasoning found among prominent survival proponents working within psychical research and parapsychology that have parallels with arguments that could be taken straight from the Christian apologetics playbook. Readers interested in their other fallacious arguments should consult my published articles linked in the first paragraph here, where I quoted verbatim such instances and (like here) bolded the names of the fallacies committed (rather than making unsupported accusations of fallacious reasoning, which anyone can do whether they are present in one’s opponents’ arguments or not).

I should note at the outset that I was not looking for such parallels when I began my critique, but felt compelled to point them out because I kept running into them. I think it is important for readers to be aware of them since they shatter the illusion promulgated by many survival proponents that they are engaging in research that adheres to scientific best practices. Note also that many passages commit multiple fallacies, and in such instances I might just name the most salient one.

1. Spinning Appeals to Contrary Evidence as Dogmatic Adherence to a Whatever-ist Agenda (It’s All Politics, Man!)

Critics of survival research, like critics of intelligent design creationism, are often accused of rigid adherence to scientism, reductionism, materialism/physicalism (“fundamaterialism“), pseudoskepticism, or some other rhetorically charged -ism in order to distract from the salient evidence that critics provide (whether it comes from neuroscience or evolutionary biology). In his first-place $500,000 prize-winning essay, for example, influential parapsychologist Jeffrey Mishlove has a section on “Scientism’s Dark Shadow” (pp. 10-13). Compare this to intelligent design creationist Denyse O’Leary or prominent Christian apologist J. P. Moreland.

Dogmatic commitment to “materialism” (rather than the argued-for pure mortalism that I defend) at all costs (rather than due to the fact that there is strong evidence that an idea is true) is said to be the driving force for doubting survival after death, paranormal phenomena, intelligent design, or what have you, because if a proponent frames the issue as their quasi-religion, then that proponent never has to talk about the evidence that their opponents offer for their conclusions. Instead, you can rile up your base (instead of addressing everyone) with rhetoric about the injustice of the materialist agenda:

It would be an interesting data dive to find out how many of those who publish in survival research also publish in the creationist literature since the fallacious arguments are largely the same. You can’t make this stuff up…

Throughout my 2022 exchanges with psychical researchers, I pointed out instances where survival researchers repeatedly attribute skepticism about life after death, almost without fail, to a “dogmatic adherence to a quasi-religious ‘physicalism'” (p. 804n4). As I noted in the exchange (and previously), I don’t even seek to defend materialism/physicalism in the first place, no matter how often psychical researchers attribute this position to me. I simply point out that our best evidence makes it highly likely that human consciousness requires a functioning brain, and therefore, in all probability, one’s individual consciousness ceases when one’s brain ceases to function. There is an argument here, and it is not at all hard to follow. It’s just easier to resist it by pretending that the argument was never made.

So I don’t even aim to defend materialism/physicalism. But even if I did, there’s an uncharitable assumption here that, for one’s opponents at least, the -ism comes first and the evidence presented is only offered in the service of defending it, come what may. But why assume the worst of those whose conclusions differ from your own? Don’t people often defend a certain point of view because the evidence suggests that it is true? Many -isms are simply shorthand for positions that have been scientifically established. One idea about the relationship between celestial bodies in our solar system has been dubbed heliocentrism, allowing us to label those who affirm that the Sun is the (near) center of the solar system heliocentrists. But just because we can put a label on them doesn’t indicate that they are married to the concept; rather, they accept it because what the label refers to is what the evidence strongly indicates is true. Another conceptual label, this one affirming that the primary drivers of the diversity of life on Earth are known natural processes, is “Darwinism.” Ideas suffixed with -ism aren’t thereby automatically rendered faith-based belief systems, dogmatically held or otherwise.

Similar points apply to the use of the term “worldview.” Those in international relations could be said to accept (and even promote!) a certain geopolitical worldview, for example, but that doesn’t mean that their points of view aren’t heavily informed by our best evidence about the state of the world. Given this undeniable reality, why not address the evidence and arguments offered for a point of view, rather than dismissing a point a view merely because a simplifying label can be put on it? Anyone can be accused, with or without justification, of rigidly holding a point of view. Such accusations are totally irrelevant red herrings when your opponents offer rational grounds for holding their views. Why not address those grounds, then? Deflecting the responsibility of doing so is just a red flag that one lacks good reason to reject an opponent’s position.

When tribalistic survival proponents talk about me (instead of to me), they often present variations of a similar fallacious argument that runs something like this: ‘If even one near-death experience (NDE) demonstrated veridical paranormal perception, Augustine’s position would be refuted. Therefore he will always deny that any instances of veridical paranormal perception have been demonstrated.’ The first sentence expresses a true conditional statement—emphasis on “if.” The second sentence conjectures, on no grounds whatsoever, that the hypothesis that I defend in light of what we know now is a hypothesis that I am (for some unfathomable reason) wedded to until the end of time. Here’s a real-world example:

Inaccurate conjectures about my “manner of perceiving” aside, changing the subject from how to answer my arguments to the most rhetorically convenient speculation about my psychological needs is clearly an ad hominem fallacy. To keep things simple, consider my hypothetical example. It’s true that all that it would take is one “white crow” to overturn my evidence-based stance on veridical paranormal perception during NDEs (or perhaps discarnate personal survival more generally). But rather than undermining it, that fact supports my position on the issue. Why? Because conditional statements concern in principle truths about hypothetical scenarios (hence the “if”). They tell us nothing about what has actually been found to be the case in practice. Thus we need more than simply one claimed white crow—we need a scientifically verified white crow. And whether or not we have the latter is not up to me to decide in the first place, but up to the scientific community as a whole. This makes uncharitable speculations about my psychological needs entirely irrelevant (and I’m quite capable of changing my mind about any number of issues so long as I’m presented with good grounds to rethink them, thank you very much). The fact that survival researchers cannot point to any scientifically established white crows on this issue, despite the fact that such instances are perfectly conceivable, is what supports my position. And that fact has nothing to do with features of my psychology. Indeed, it has nothing to do with me at all. Rather, it concerns the state of the survival evidence, whose features are what they are completely independently of my views or my (or anyone else’s) willingness to acknowledge those features.

To see that this is poor reasoning, one need only consider the ridiculous parallel argument that would result from the beginnings: ‘If even one authentic satellite video showed the Earth as a flat disk, Augustine’s round-Earthism would be refuted.’ Indeed—but so what? Can you actually produce such evidence, or not? (To say nothing of the authenticated evidence that shows the opposite, which an honest evidential assessment would also have to admit into evidence.) Had the BICS contestants actually met their directive to provide evidence “beyond a reasonable doubt” of the discarnate survival of individual human consciousness after death, nothing that I might have to say on the matter would be material. That the BICS contestants did not do this is evident from the simple fact that geographers have come to a consensus that the Earth is round, but the BICS contestants’ “evidence” did not result in a consensus among psychologists or other cognitive scientists that human consciousness survives death. Albert Einstein’s “annus mirabilis” papers produced a revolution in physics. The BICS contest produced nothing even close to that for the scientific study of the mind. And the difference in their respective impacts had nothing to do with me or any other skeptics. The BICS contestants simply did not deliver the goods because there were no goods available to them to deliver. As I wrote in my reply to Braude and co.: “The issue was never about what any particular person believes, but about how discarnate personal survival could move from an item of personal belief to an item of scientific knowledge” (p. 422).

2. Changing the Subject to Critics’ Motivations

As I point out in an endnote, survival researchers like prominent parapsychologist Stephen Braude often use stigmatizing red herrings to change the subject from the real crux of the issue—the state of the survival evidence—to the immaterial issue of “the psychological disposition of any particular person or tribe” (p. 422):

Ironically, in the same paragraph where Braude et al. accuse me of committing the same fallacies that I extracted verbatim from the BICS essays—which is itself an ad hominem tu quoque [“you do it, too!”] if there ever was one—they add: “Augustine seems to infer not simply that nothing psychic was happening during the tests of OBErs and NDErs [out-of-body and near-death experiencers], but more likely, given his broad skepticism about things paranormal, that nothing psychic could occur.” That’s an odd thing to say of tests that, as a contingent matter of fact, have historically failed to reveal any evidence of psi [i.e., the paranormal]. Apart from an aversion to the principle of charity, what prompts this attribution—the fact that other skeptics have expressed this? (e.g., Alcock & Reber, 2019). The reason why “Augustine never clarifies this” is because it exists in their heads, not in my BICS critique. (p. 432n17)

As I noted in the main text, the issue was never about any particular person’s motivations; rather, the issue was “whether or not survival researchers have delivered the kind of evidence that would give the scientific community reason to think that there is something in this research in need of novel kinds of explanation. What scientific conclusions does the evidence warrant?” (p. 422) If the evidence on offer really could withstand scientific scrutiny, why change the subject?

Similarly, in his winter commentary, biologist Michael Nahm wrote: “Regarding Augustine, I perfectly agree with Braude et al. (2022) and previous critics of his work who already demonstrated earlier that his manner of arguing is selective and biased indeed” (p. 787). Of course, anyone can claim—or simply repeat/cite the unsupported claims of others—that an opponent is “biased” for merely defending an alternative position. Are those who say that the Earth is round (an oblate spheroid) “biased” since they take a position on the issue of the Earth’s shape? Are those who take the opposite position somehow magically unbiased, despite having a position to defend themselves, and a stake in maintaining their position? On the playground one might expect opponents to fall back on childish discreditation or lazy generic accusations of bias (that anyone with a different view could be accused of for having—gasp!—provided arguments for their views), but it is unbefitting of scientific debates about evidence.

Do proponents really believe that researchers who’ve devoted the bulk of their research careers to trying to vindicate the existence of life after death are equally open to the possibility that maybe, quite possibly, there is no afterlife? Their reputations are no less tied to their long-held positions than those of skeptics—and arguably more so since skeptics tend to not to have decades-long careers whose sole purpose is to find evidence for a particular point of view on a single issue. In this respect it’s notable that survival researchers are often inducted into psychical research societies, but there are no “extinction researchers” inducted into neuroscientific research societies surrounding them.

Moreover, there’s a distinction between arguing for a position because your career requires you to do so and defending a position (within one’s career or otherwise) because one believes that it is true on the basis of evidence that can be clearly spelled out and argued, making accusations of bias all the more irrelevant. Why automatically assume the worse motivation when someone provides reasons for views that you happen to disagree with (but under different circumstances, or in the future, might come to agree with)? Why not tell readers why the cited reasons are wrong, instead of killing the messenger?

There are those who research the mind’s relationship to a functioning brain, of course, in cognitive neuroscience and philosophy of mind with no particular professional interest in the survival of human consciousness after death, so one might anticipate that their (particularly consensus) conclusions ought have more weight (prima facie) than the conclusions of those triggered to explicitly resist certain conclusions whenever they fail to serve making a case in favor of survival after death. In this sense the relationship of survival research to cognitive neuroscience or the philosophy of mind is akin to the relationship between “creation research” and evolutionary biology or the philosophy of biology.

How many Christian apologists speculate about the depraved motives of atheists who purportedly deny God’s existence in order to excuse their immorality or sexual deviancy, rather than address atheists’ arguments?

3. Different Perspectives Spun as Rationalizations for Immoral Behavior

In my opening BICS critique, I noted how out-of-body experience (OBE) researcher and parapsychologist Charles Tart proposed that materialists would ask “Why bother?” if confronted by a drowning child, parapsychologist Dean Radin and coauthors claimed in their BICS essay that acknowledging that we finite creatures might not exist for all eternity “leads to exaggerations of the worst vices of humanity: envy, greed, and selfishness,” and so on. These fallacious arguments from consequences are ubiquitous among creationists and Christian apologists. Compare Larry Arnhart‘s reporting in the old Salon article “Assault on Evolution: The Religious Right Takes its Best Scientific Shot at Darwin with ‘Intelligent Design’ Theory” (February 28, 2001):

At the [three-hour] briefing [with the US Congress], Nancy Pearcey quoted the lyrics of a song by the Bloodhound Gang—”You and me, baby, ain’t nothin’ but mammals, so let’s do it like they do it on the Discovery Channel.” This, she warned, is what we can expect if the materialism of the Darwinians persuades us that we are merely mammals, rather than beings elevated above other animals and created in the image of God. She urged the congressmen in her audience to remember that the US legal system is grounded in the belief in a creator as the ultimate source of moral law. Darwinism, by undermining that belief, is morally and legally dangerous.

A verbatim quote of the late creationist Henry Morris making parallel fallacious arguments is provided in the critique itself. And within Christian apologetics that is not specifically creationist, how often do we encounter tropes about how Adolf Hitler was an atheist (untrue) or that Joseph Stalin was an atheist (true but irrelevant)?

4. You’re Suppressing My Beliefs if You Don’t Promote Them!

Unsatisfied with simply characterizing “materialism” as a “nihilistic philosophy,” Radin and co. go on to add:

The cynical quip, “He who dies with the most toys, wins,” captures the harmful effects of absorbing a picture of reality that children begin to learn as soon as they enter the (secular) educational system, and that is inculcated in adults for the rest of their lives.

But as I point out in my opening critique, refraining from inculcating otherworldly beliefs is not the equivalent of inculcating anti-otherworldly beliefs. Rather, it is neutrality or respect for tolerating the diversity of individual opinions on issues that have not been scientifically established. Failing to promote your view is not equivalent to promoting others’ views, period. This fallacious argument is nothing new, of course:

5. Coloring Morally Neutral Concepts with Immoral Aspects

Under the previous heading, we’ve just seen Radin and co.’s conflation of materialism, sometimes defined as the view that everything is physical (which one need not even affirm to doubt life after death), with materialistic consumerism. In my opening BICS critique, I mentioned in passing how OBE researcher and parapsychologist Charles Tart did the same thing in his The End of Materialism: How Evidence of the Paranormal is Bringing Science and Spirit Together. In his characterization of the supposed consequences of accepting “scientistic materialism” as true, Tart writes:

Long-term, I really needn’t worry about the degradation of the planet, global warming, overpopulation, and so on…. I’ll likely be dead when civilization collapses. So I’ll use resources to make myself happy now and not worry about the distant future. If I feel any guilt about this or worry about my descendants, that’s meaningless social conditioning and biological built-ins manifesting: I should ignore them and get on with looking out for number one. (2009, pp. 299-300)

Recall Arnhart’s paraphrase of Nancy Pearcey a few headings above that the biological theory of evolution by natural selection “is morally and legally dangerous,” as if this consequence—even if it were true—would have any bearing on the truths of biology.

Continued in part two…