Black Holes and the Problem of Evil

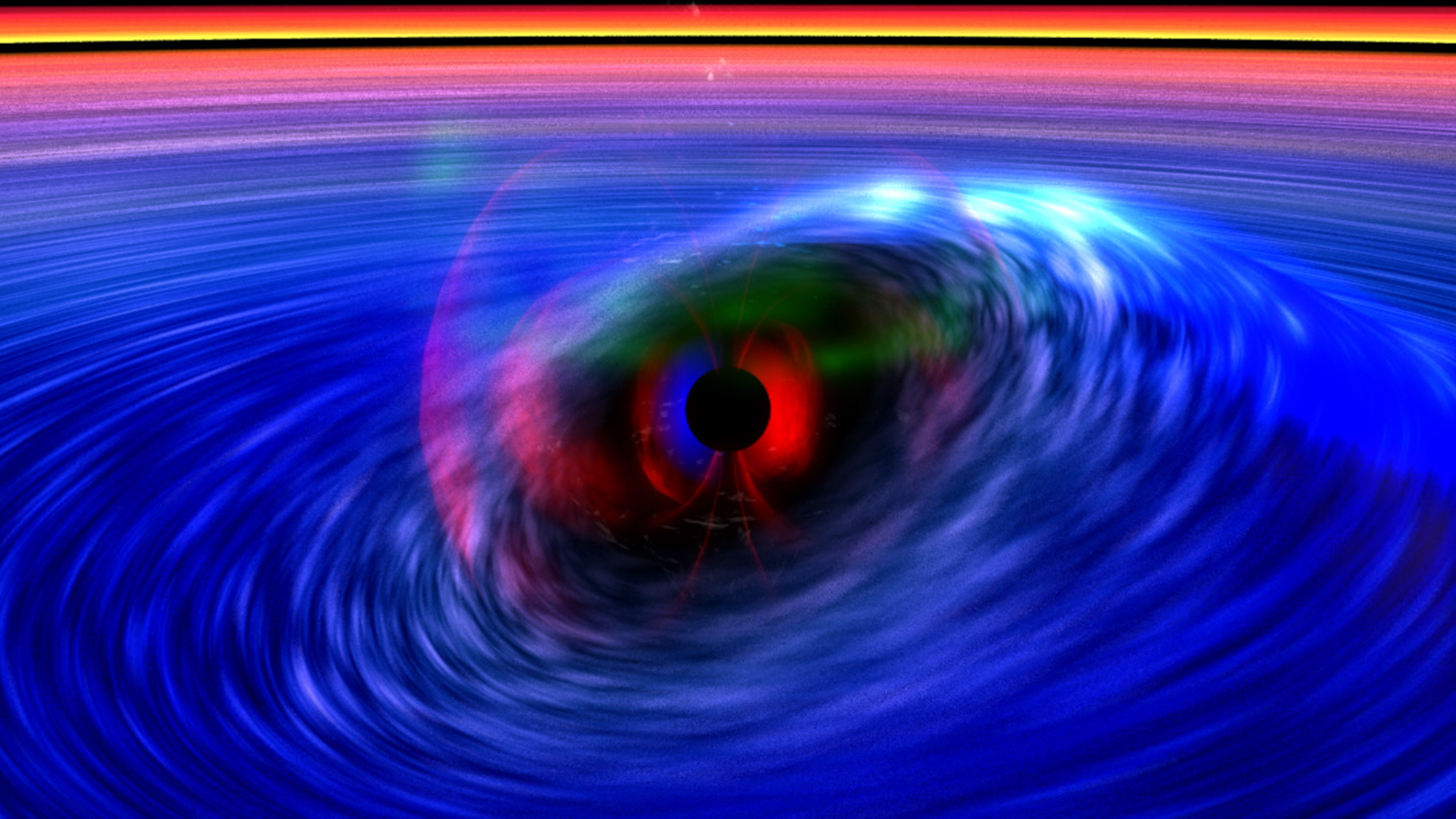

Data produced by the Hubble Space Telescope show that the brightest supernova ever recorded was actually a star being torn apart by a black hole in what is being called the ASASSN-15lh event.

This has a high “coolness factor” for astronomy enthusiasts. But I couldn’t help but wonder a little whether there were any planets in that ill-fated solar system with life on them. Suppose such a catastrophe were to befall Earth – what would be the theological implications? This would be a purely hypothetical or speculative instance of the Problem of Evil, but certainly one of massive scale. What would be the theistic response to the possibility of such an event?

Here are several possibilities:

(A) It couldn’t happen.

God loves the Earth too much. The destruction of Earth by a black hole is scientifically possible, but theologically impossible. Similarly, if God has seen fit to have intelligent life exist elsewhere in the universe, he would also prevent the total destruction of alien life just as he would prevent the total destruction of life on Earth.

Needless to say, I am unimpressed by such an a priori argument strategy. To say that we can know with confidence that the ASASSN-15lh event did not destroy any intelligent civilizations from the comfort of our Earthly armchairs seems too callously cavalier for my tastes.

(B) It would be deserved

Just as God (in the story of the Noahic flood) destroyed all Earthly civilizations out of righteous wrath over their wickedness, the destruction of an alien planet by black hole would only be divinely permitted if that civilization were massively sinful. Although God promised never to destroy the Earth by flood, destruction of the Earth by black hole is still on the table as a possibility.

This second response is just as unsatisfactory as the first. Is it really plausible that we can know, from millions of light-years distance, the extent of an alien civilization’s wickedness entirely by what God allows to happen to it? When we read about disaster befalling some location on Earth, only contemptible zealous reprobates think “well, that’s what happens when you allow gays to get married.” This is not relevantly different.

The theist can always, of course, by pointing out that one imaginative hypothesis deserves another: If I am going to float the suggestion that there may have been intelligent life in that distant solar system, the theist can float the suggestion that perhaps they were cruel and aggressive with plans to dominate the rest of the universe, Earth included. God, then, permitted their destruction for the morally justifiable reason of preserving other intelligent worlds. This reminds me too much of theists who respond to the question of why God permits children to die of cancer by suggesting that maybe they were going to grow up to be as evil as Hitler (which only raises the further question of why God allowed Hitler to grow up, then).

(C) Skeptical theism

Our knowledge of good and evil is so puny in comparison with God’s that we’re in no position to say that destruction of an inhabited world by black hole would be a morally bad thing for God to permit.

I have little enough patience with skeptical theism as it is, but at this point I think the appropriate reaction is to despair of the skeptical theist being able to use the terms “good” and “bad” in a truly meaningful way. To respond to the destruction of an entire planet (whether or not it is Earth) by saying, “for all we know it’s all for the best” is to abandon meaningful ethical discourse.

(D) If

It is reputed that Philip II of Macedon sent a message to Sparta saying, “Surrender immediately, for if my armies capture your lands, they will destroy your farms, kill your people, and raze your city.” The response from Sparta was the single word, “If.” The whole scenario here is purely hypothetical. There is no reason to think either that any intelligent alien civilizations have been destroyed by a black hole or that this is to be the fate of Earth.

This response concedes that the destruction of an inhabited planet by black hole would, in fact, count as reason to think that God does not exist. The conditional, “if an inhabited planet were to be destroyed by black hole, then God probably does not exist” is true, but has an unsatisfied antecedent, on this view. This is interesting because it concedes the possibility of empirical disconfirmation of God’s existence.

There are some atheists who think we don’t need to look beyond the surface of the Earth to find abundant disconfirmation of God’s existence. For them, there is already enough “bad stuff” to be found that they think the antecedent of a conditional like “if enough bad stuff were to happen in the world, then God probably does not exist” is satisfied. There are theists, too, who think this conditional is true, but are unpersuaded that the antecedent is satisfied. But at least there is common ground here. Perhaps, then, it may turn out to be true, after all, that science is capable of addressing the question of God’s existence? Just keep studying black holes.